Blog

-

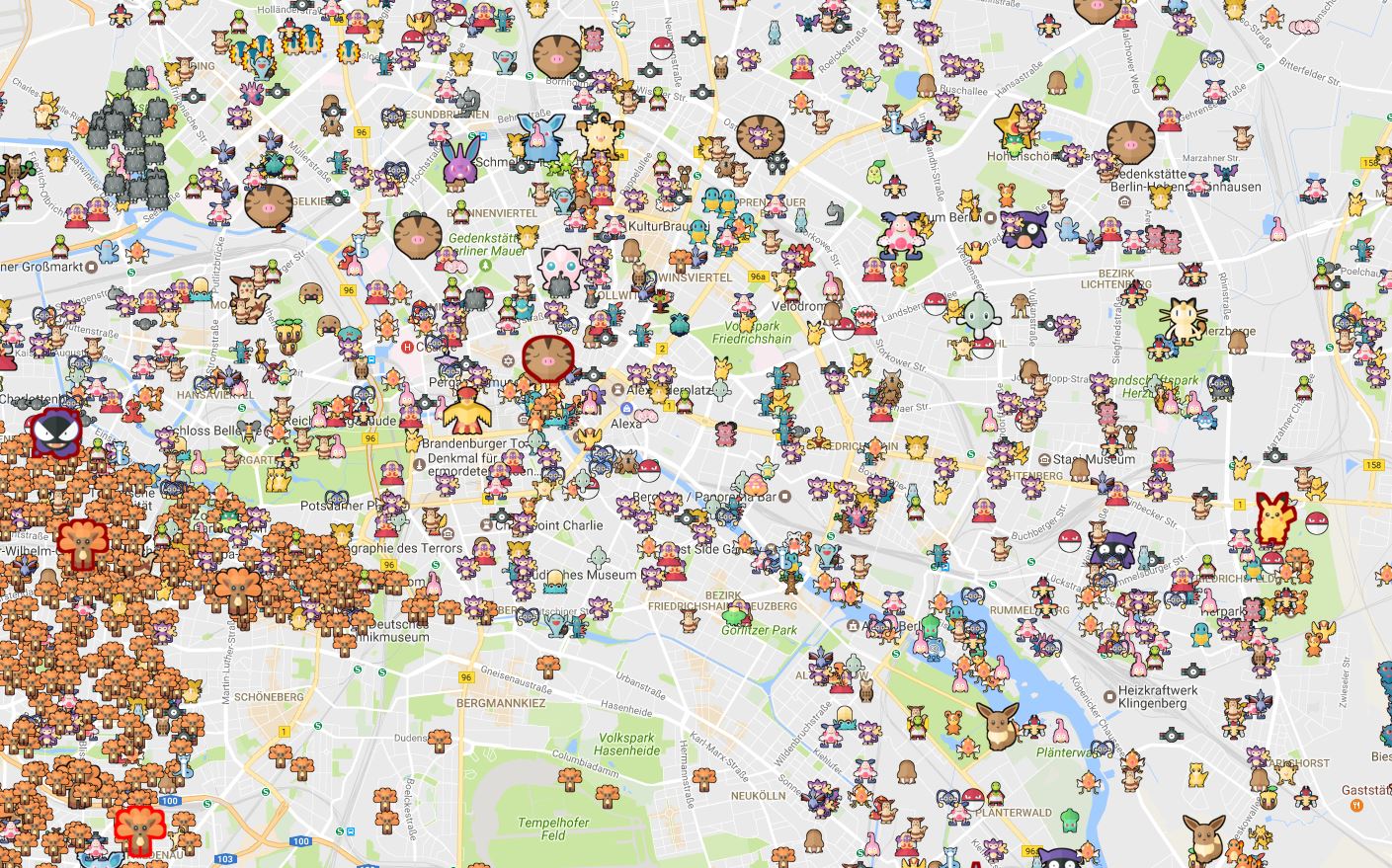

Pokemon Go and the ethics of map data

After a decade developing Google Maps, programming innovator John Hanke branched off a new software company, Niantic, to realise his dream of turning Earth into the ultimate game map. “When we started Niantic, we had the idea of people exploring the world – exercising and engaging with other people. We thought that if our games do that, then people will be better off than they were before.”Both companies had high hopes for Pokémon Go, but neither were prepared for what was about to unfold. “The amount of money that we forecast the game would make in the first year, we made within the first week of launch,” Hanke recalls, shaking his head in disbelief. “The late-night comedians, politicians, morning-show hosts were all mentioning it. It was great to be part of the cultural conversation.”

after newsletter promotion

But just as there are ethical implications in surveilling the world to amass map data, Niantic had to think hard about its responsibilities if it were to be sending loads of kids on an unsupervised treasure hunt via a device that monitors their location. “Companies have to have a position on how their technology is going to be used,” John says. “I think it’s a trap to say, ‘we’re agnostic, we’re putting the technology out there, somebody might do something bad with it, other people might do something good with it.’ No, I don’t believe that. It is incumbent upon the creators to have a thesis about how it’s going to get used, how it’s going to make the world a better place and why it deserves to exist … It’s really, I think, the responsibility of the CEOs and the board to kind of take control of what’s happening with their technology and be intentional about it.”

John Hanke during his keynote speech at the Mobile World Congress in Barcelona, Spain in February 2017. Photograph: Paul Hanna/Reuters How does Hanke weigh up these ethical responsibilities as a tech company? “We’ve worked hard to build the trust of our playing community – and protecting their privacy is an important part of that,” he says. “We only retain location information for the time necessary to operate the game and plan for in-game resources they interact with. After that, we will either remove it from our systems or anonymise it so that it cannot be associated with individual players. We also don’t sell any user information to third parties.”

-

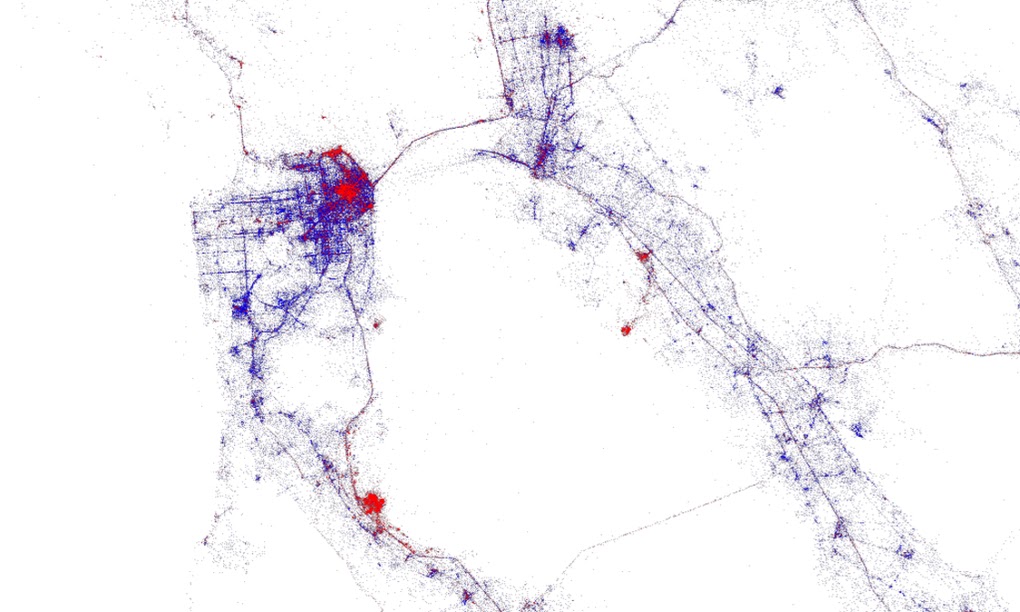

Eric Fishcer: City heat maps

Fischer, a ‘data artist’, applies Twitter data gleaned from Gnip in the mapping tool MapBox to help visualise where temporary visitors go in cities. San Francisco (top left) and the Golden Gate bridge, for example, attract far more non-locals than Oakland across the bay. The concentration of red to the south is San Jose.

Explore his world map here https://labs.mapbox.com/labs/twitter-gnip/locals/#

-

Robert Macfarlane: “Paths are human, they are traces of our relationships.”

Nature author Robert Macfarlane has written recently about the inherent poetry of desire paths. In his 2012 book The Old Ways: A Journey on Foot, Macfarlane calls them “elective easements” and says, “Paths are human; they are traces of our relationships.”“Desire paths have been created by enthusiastic dogs in back gardens, by superstitious humans avoiding scaffolding and by students seeking shortcuts to class. Yet while illicit trails may have marked the easier (i.e. shorter) route for centuries, the pandemic has turned them into physical markers of our distance. Desire paths are no longer about making life easier for ourselves, but about preserving life for everyone.” -

Holloways

In Europe and the Middle East, ancient sunken lanes known as ‘holloways‘ (or: hollow ways) represent a particularly extreme expression of the desire path phenomenon. Many of these semi-subterranean routes have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, eventually appearing more like a tunnel than a pathway.

Holloways generally reflect a confluence of conditions, including heavier usage by vehicles, softer ground materials and high desirability (for instance: a major route between towns or cities).

In some cases they also reflect a greater degree of intentionality, starting organically then being manually carved out as irrigation channels or for use as trenches during times of war.(Source: https://99percentinvisible.org/article/least-resistance-desire-paths-can-lead-better-design/)

Talking with a local historical group recently I have discovered that there are some hollow ways in Nottinghamshire including one called Rob Way between Hartswell and Oxton, which I will visit and document soon.

-

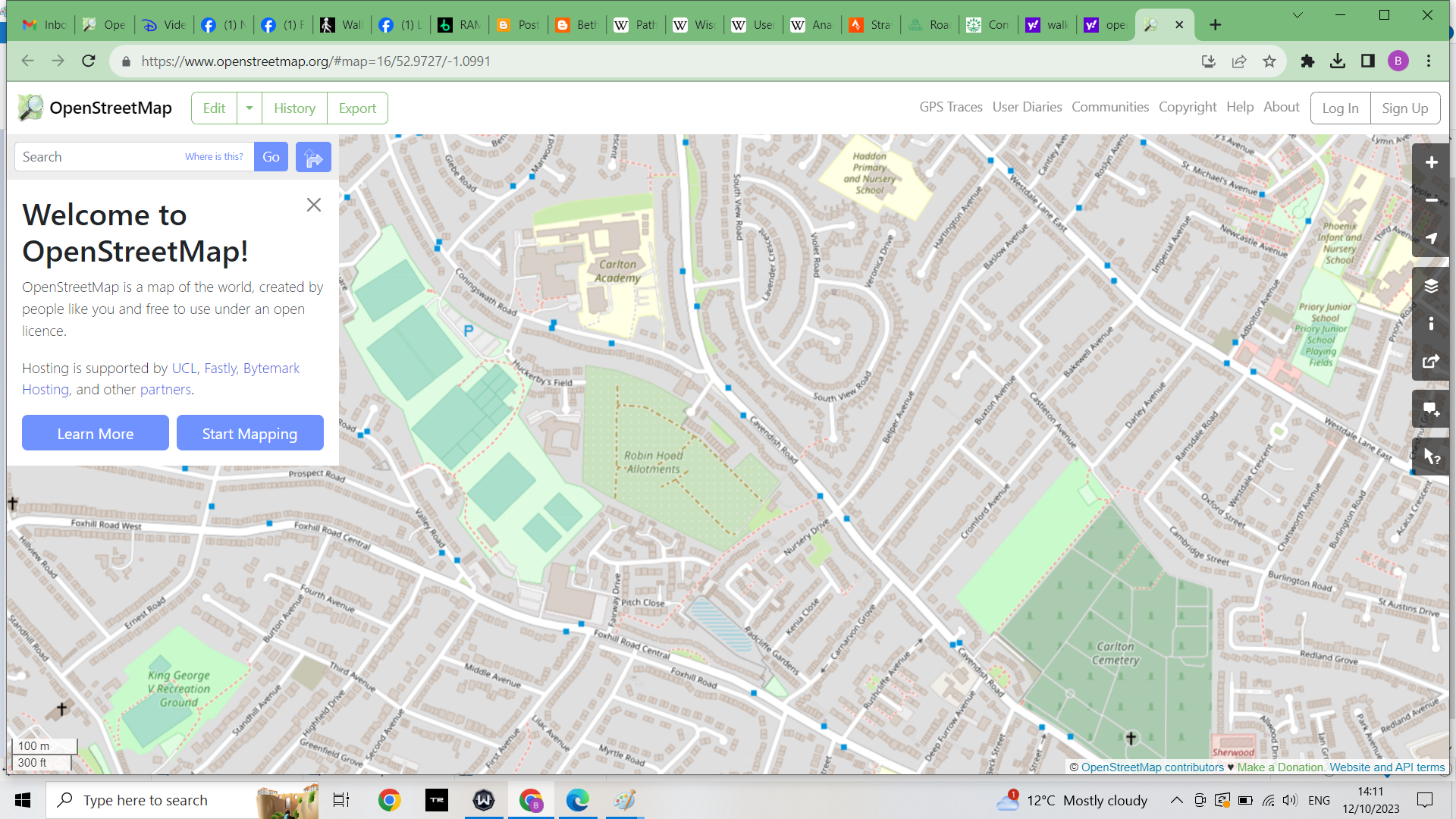

OpenStreetMap (OSM): An honest open source map database

OpenStreetMap (OSM) is an international, crowd-sourced project to create a free map of the world – since 2004, thousands of volunteers have input data about roads, railways, rivers and yes, desire paths.“People like you and me have mapped 35,000-plus paths as desire paths or informal paths worldwide, including around 1,500 mapped in the UK,” says Dorothea Kazazi, a communications volunteer for OSM. Kazazi explains that desire paths should be “reasonably permanent” to be added to the map, but says anyone can add one at any time. “We map the world as it is,” she says.”According to OSM, most of the UK’s desire paths are in Nottingham and Leeds. It’s unclear if this is because there are actually more desire paths in these areas, or if these locations are simply home to avid OSM users. Kazazi puts me in touch with a Nottingham man who has documented a large number of desire paths, but unfortunately he declines to explain his motivations.”So what is OSM?OpenStreetMap UK (OSMUK) is a community and non-profit organisation that represents all mappers in the United Kingdom, including Northern Ireland, the Isle of Man and Channel Islands as well as the interests of the map itself. We hope to share this with you and to help you to become part of the OpenStreetMap family.OpenStreetMap (OSM) is a collaborative project where individuals and organisations contribute to a free and editable map of the world. It is rich in local knowledge and includes an incredible level of detail that continues to grow every day. Although it is possible to use OpenStreetMap just as a map, it becomes really useful when treated as a databaseWhat if a map could be built with the collective knowledge of thousands of individuals and organisations? With OpenStreetMap it can. We pride ourselves in the richness of the data collected by thousands of partners all experienced in their own fields. From individuals who add local knowledge to the map in their home-town, to organisations from across the public and private sector who add information collected from their day to day activities, OpenStreetMap includes the full range of contributors. These same organisations, and many more, also benefit from using the map and the underlying data. From apps to movies, OpenStreetMap is being used everywhere.Most maps you think of as free actually have legal or technical restrictions on their use, holding back people and organisations from using them in creative, productive, or unexpected ways. They are often also supported by advertising. OpenStreetMap is different – we believe that you should be able to copy, distribute, transmit, and adapt our data with minimal fuss. With thousands of partners all helping to keep the map up to date, OpenStreetMap need not advertise. What is shown on the map reflects what is on the ground and we will never give greater precedence to paid advertisers.(Source: https://osmuk.org/)