I understood this theme to explore the idea that for some artists, their process in terms of visual language is integral to understanding their work. It’s another area of discussion and a consideration for making that I am fascinated by as I really really enjoy process and the making that “proceeds” art; it can be more important for me than any resulting work.

In a more ephemeral way, it explores fragile ideas in relation to art like truth, promise, expectation, what is fair, what has value, what and who deserves recognition and why. It really pokes at what art is, what it can be. What it’s allowed to be. I am excited about looking at and pushing these constructs and boundaries, playing with their elastic limit.

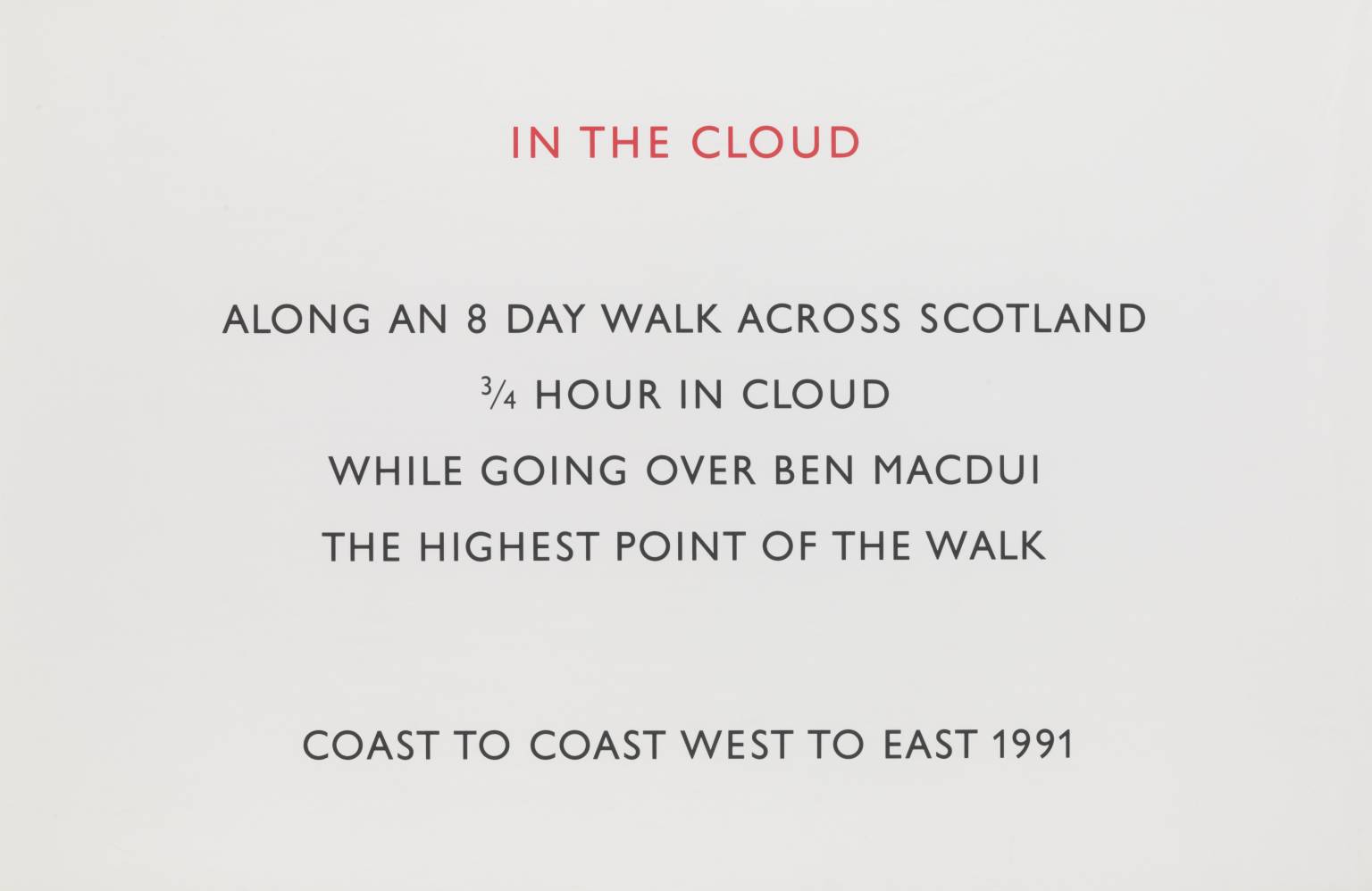

Richard Long’s text pieces are a good way to further consider the theme of process.

“In the Cloud describes the moment Long walked over Ben Macdui, the tallest peak in the Cairngorms, and records how much time the artist spent enveloped in cloud. Another text work, A Cloudless Walk 1996 (Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh), describes a walk determined by the length of time the artist walked until he reached a cloud.

The textual description of the walk provided by In the Cloud avoids mentioning extraneous details or using verbose language. Long has stated that ‘A text is a description, or story, of a work in the landscape. It is the simplest and most elegant way to present a particular idea, which could be a walk, or a sculpture, or both’ (cited in Tufnell 2007, p.45). The artist’s first text work was made in 1969 for the seminal exhibition of conceptual art When Attitudes Become Form: Live in Your Head at the Kunsthalle Bern (see Wallis 2009, p.47). That work, called A Walking Tour in the Berner Oberland: When Attitudes Become Form (whereabouts unknown), consisted of a text that included the first half of the work’s title proceeded by the artist’s name and the dates on which the ‘walking tour’ took place. In the same way as In the Cloud, this early work recorded a walk in pared-down and impersonal language. This use of language is characteristic of conceptualism, but for Long it is essential that the idea presented in the text has been executed, whereas other conceptual artists who make text-based work, such as Lawrence Weiner, privilege the idea over the possible realisation of an action. Regarding the use of text in his work, Long has commented:

‘One of the reasons why I started making text works is because it gave me another possibility, not using the camera or not necessarily making a sculpture. I can use words and they can give me different possibilities than I would get from using a camera. So, taking photographs does a certain type of job, records one moment, makes an image. And words do a different job. They can usually record the whole idea of a walk. They have a different function, sometimes a more complete function.’ (Cited in Tufnell 2007, p.69.)”

How do we know he even did the walk? Would it matter if he hadn’t walked at all? Would this text piece still have value? Is it art and why?

Process is an interesting thing to consider as an artist because it hits lots of ideas around professionalism and work ethic. Some folk get annoyed that artists, like Damien Hirst, would employ other people to make their work for them. They find it inauthentic, like cheating. I personally feel like as long as the artist, whoever they are, is being acknowledged and credited, it’s all fair and dandy. It’s collaboration.

A type of making process that I naturally relate to is action or gestural painting.

“Gestural’ is a term employed to characterise the technique of applying paint with bold, sweeping brush strokes in a free and expressive manner.

The term ‘gestural’ initially emerged to describe the painting style of abstract expressionist artists like Jackson Pollock, Willem de Kooning, Franz Kline, Robert Motherwell, Hans Hofmann, and others, often referred to as ‘action painters.’ In Pollock’s case, he might use a dried brush, a stick, or even pour paint directly from a can, creating a sense that the artist physically acted out their inner impulses.

The idea was that the viewer could perceive something of the artist’s emotions or state of mind through the resulting paint marks. De Kooning explained that he painted in this manner to continually infuse his work with various elements, such as drama, anger, pain, and love, allowing the viewer to interpret these emotions or ideas through their own eyes.

This approach to painting draws its origins from expressionism and automatism, notably the work of Joan Miró. In his 1970 history of abstract expressionism, Irvine Sandler distinguished two branches within the movement: the ‘gesture painters’ and the ‘colour field’ painters.”

A gestural painter that I adore is Franz Kline, the American painter from the New York School.

Henry H II, 1959-60

West Brand, 1960

“It is widely believed that Kline’s most recognizable style derived from a suggestion made to him by his friend and creative influence, Willem de Kooning. De Kooning’s wife Elaine gave a romanticized account of the event, claiming that, in 1948, de Kooning advised an artistically frustrated Kline to project a sketch onto the wall of his studio, using a Bell–Opticon projector. Kline described the projection as such:

“A four by five inch black drawing of a rocking chair…loomed in gigantic black strokes which eradicated any image, the strokes expanding as entities in themselves, unrelated to any entity but that of their own existence.”